(Preview of a chapter from volume one of Organize to Win

Shortly before becoming a wilderness activist, I retired as a federal manager. During my 25-year career in government service, I was responsible for resolving turf conflicts within agencies, oversaw the evaluation of managers and supervisors, and conducted scores of audits of local and regional offices. Early in my tenure, I supervised a federal field office similar to those operated by the U.S. Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management (BLM). So, I acquired insight into how government managers think, behave, and deal with the day-to-day pressures inside federal agencies. Subsequently, as an activist, I dealt continuously with state and federal managers for 13 years.

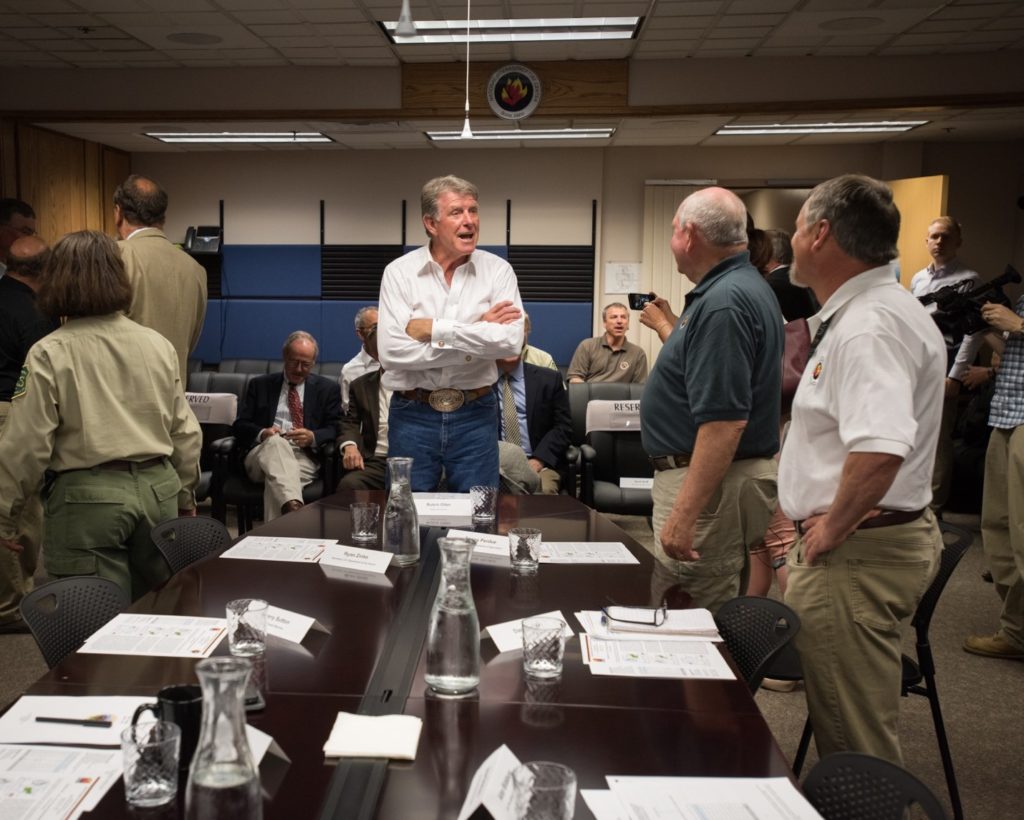

One of the most important lessons I’ve learned as both an insider and outsider is this: Environmental advocates always have a better chance of influencing government decisions when they develop good personal relations with the relevant government officials. Although this seems obvious, activists often assume an adversarial posture when dealing with bureaucrats, which greatly reduces the prospects for success.

While public employees in general are honest and hard-working, when environmental laws that protect very valuable natural resources are involved, the political pressure on agencies to bend and even break the law to generate more economic activity can become too much to resist. This is when environmentalists become the instrument by which the public forces agencies back into legal behavior. Environmentalists are to public agencies as plumbers are to blocked sewer lines; the interactions and processes in both situations are often messy, stressful, and unpleasant. In most relationships, agency employees will, and should, avoid getting too friendly, and may even be hostile to you. But occasionally, when agencies are clearly violating the law, and the employees know it, you may find people inside agencies that will help you. However, in most situations, agency managers, behind the scenes, will be helping the companies and politicians who benefit from their wrong doing. Also, more than one federal manger has promised me confidentially that he would help me; later, pressure from his bosses forced him to promise an opponent the exact opposite. Paradoxically, the ostensibly “greener” agencies (like the U.S. Forest Service) are more likely to fail to keep promises than the agencies who often seem unconflicted about their bad behavior (like the BLM).

But, regardless of the agency, activists, bitterly contending with a state and federal agency, often assume that the anti-environmental behaviors of the agency are subscribed to by its employees. Nothing is further from the truth. Most people who work for land management agencies or are professionals in the natural sciences do so because they truly care about nature and the environment. Yet, almost every environmental outrage involves some scientist watering-down or rewriting reports to deliberately conceal and minimize environmental impacts. Over time, this can make the staff of land management agencies frustrated and even ashamed of themselves. So, when you approach staff off-the-record for help in detecting a project’s weaknesses, you might be surprised by their helpfulness. Agency managers, even those doing very bad things on their own agency’s land, may nevertheless be willing to help you with an issue on another agency’s land. Often, however, managers won’t help activists because they have learned the hard way that some activists are blabbermouths. People won’t confide in you if they fear you will hurt them. But if they sense you are discreet and will guarantee their anonymity, they will often tell you all they know.

Scientists, unwilling to help you solve problems in their agency, may be more than willing to help you stop bad projects in another’s. If you are involved with a campaign against one branch of government and nearby land is under the control of another, often the neighboring agency may have a lot of helpful scientific information buried in their file cabinets. For example, scientists preparing biological plans for a state agency often do surveys on a regional or watershed basis and possess critical information on endangered species on nearby federal land. This can be about wide-ranging animals, endemic plant species, geology or hydrology information, and it is often information they are happy to share. In locations where the political process has yet not been captured by the particular development or extractive industry that needs regulation, as in the New York campaign that stopped the introduction of fracking, university scientists actually lead tough environmental campaigns. So don’t be afraid to ask your local university “ologists” for help. A state biologist may be unable to do much to stop bad things from happening to the fish runs in a river that flows through state land. However, that same scientist may be very knowledgeable and help you protect fish upstream in that same river where it flows through neighboring federal lands.

Unfortunately, some grassroots environmental organizations never get anything but official, by-the-book answers to any question from public agencies or politicians because agency staff have learned from painful experience that if they give off-the-record information to activists, they won’t keep confidences. So, often staff don’t even give activists information that is ordinarily available to anyone. In any campaign (whether political or environmental), even opposing sides sometimes share information with each other that would look very awkward if it became public. Amateurs will sometimes betray these confidences to gain a quick headline and become forever frozen out from information.

In one case, a Democratic politician quietly told a local group that he would try to stop a controversial old growth timber sale that was supported by many of his conservative constituents in the area and later it turned out he couldn’t. The group put out a press release claiming he lied when he promised to stop the sale, thus burning the congressmen with everyone. After that, the congressman and his staff never cooperated with that group.

But if you are discreet and can use information without burning your source, it can pay huge dividends. Once I was at an agency meeting as part of a public process to classify some newly acquired state land and all morning, the lead agency scientist responded to my every attempt to find vulnerabilities in their preferred alternatives with variations of, “That’s not a problem….” He fought me on every issue.

Later, when everyone else had gone out to lunch, the two of us stayed behind (we had brought our lunches). We were alone in the meeting room with the maps and handouts between us. He said, “The issues you are raising are not really serious problems.”

I asked, “Do you know where the serious problems are?” He said, “Sure.” I responded, “Will you show them to me?” He pulled the map over and pointed out the critical and fatal weaknesses in their alternatives. Turns out he had been unsuccessfully trying to get them changed through the agency’s internal channels all along. Armed with his information, which involved egregious violations of the agency’s own biological survey procedures for an animal I was not aware even existed in the area let alone had strict protocol for, I was able to get his agency to agree to all my concerns.

When you use “inside” information, always be careful. Never inadvertently disclose your source. Once I made the mistake of asking for a “lost” document about a gross agency violation with such specificity the agency could tell I could only have found out about it from one person. My source almost lost his job and never was friendly again, and we had been good friends.

As a class, scientists have a hard time not telling the truth. You should approach them directly as individuals, rather than in their official role. Ask questions like, “How would you try to stop this project, if you were me?” or “What questions should I ask you that I haven’t?” The best kept secret in grassroots environmentalism is that the vulnerabilities of many projects are brought to our attention by agency scientists who are in the position to know what the real facts are.

On the purely political level, in small rural counties that must contend with “wise use” politicians, employees of land management agencies often represent a large bloc of voters. In one rural county in New Mexico famous for anti-environmental rhetoric from its county commissioners, such employees are, in fact, the largest single bloc of voters. Since public employees can usually engage in electoral politics and are generally progressive and educated, they represent the best possible source of votes to counter local “wise-use” candidates at election time. The combination of local environmentalists and public employees provides the best and sometimes the only chance to oust ultra-right-wing county commissioners. Rural federal employees and their families are often as discriminated against and harassed for being ‘radical environmentalists’ as local activists are, sometimes even more so. Thus, there is a potential political community of interest between them.

I was involved with a successful campaign where local environmentalists worked in partnership with a federal agency’s union to stop a bad environmental scheme. The agency opposed the scheme, too, but could take no official position. So, the activists did the organizing and public relations and the agency’s union raised the money for the campaign.

In my experience, and every local situation is unique, the likelihood of substantial cooperation and support from managers and officials declines as you go down the chain from federal, to state, to county, to the local level. The lower you go, the more insecure, timid, and afraid officials tend to be. Of course, some land managers are evil people. Some are even personally corrupt, but this is rare. Most make bad decisions and carry them out because they feel they are forced to do so. Regardless of a person’s reputation or that of their agency, approach them with the assumption they will do the right thing. Many will rise to your expectations. On the other hand, if you approach staff with the attitude that because they are doing bad things, they are personally bad and corrupt, they will probably respond accordingly (unless they are smarter and better lobbyists than you are).

Public land managers and biologists are often forced to make decisions they know are wrong because of political pressure and come to depend on activists to stop them from doing things they feel personally terrible about. Oregon environmentalist Andy Kerr used to refer to the phenomenon of agency people secretly helping environmentalists as the “Stop me before I kill again” syndrome.

Subscribe to my blog

Download Organize To Win Vols 1, 2, & 3

My Amazon author page