There are some larger and little discussed issues around the growing trend that seeks to resolve all conflict with partnerships, roundtables, win-win and consensus processes. These approaches have not just suddenly appeared in a vacuum. America’s fundamental assumptions about the political decision-making process itself are being systematically reshaped by a new political theory called neoliberalism, which aggressively and specifically promotes these methods.

A central tenet of neoliberalism—a political theory of governmental administration—is a tendency to view the purpose of government and public processes in strictly economic terms, and to ascribe the cause of most problems to market inefficiencies and too little competition. Under this approach, all conflict is resolved by using rational, professional problem solving to find win-win, job-creating solutions. A defining characteristic of this approach is a reluctance to ascribe the cause of any problem to pervasive and systematic corruption, or to the ability of the rich and the strong to take advantage of the poor and the weak.

This theory is in sharp contrast to what activists have learned from decades of experience—a world view best summed up by Saul Alinsky (probably the 20th century’s best grassroots community organizer) who said, “We live in a world of unbelievable deceit and corruption…Giant corporations are unbelievably oppressive and follow a win-lose philosophy…. [and] will go to any length to make more money.” *

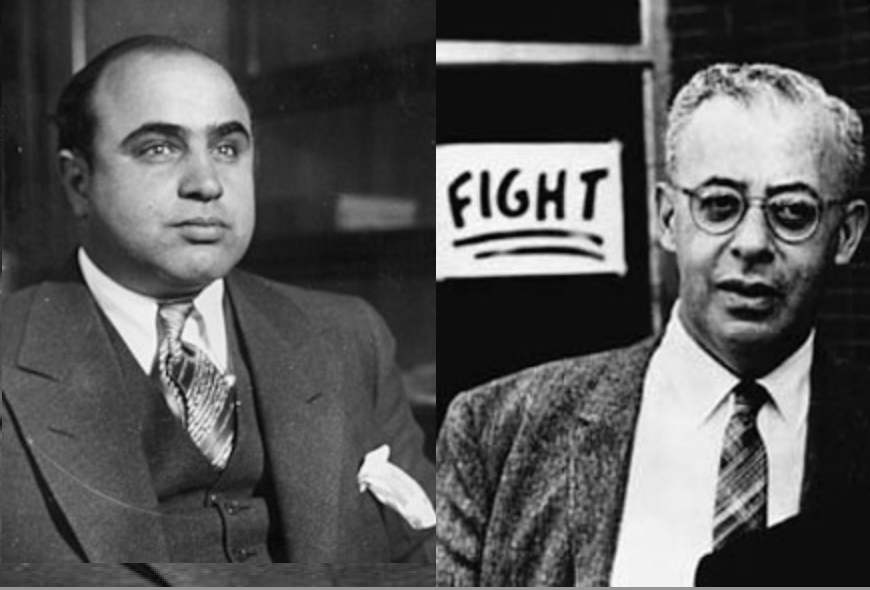

In juxtaposition to the world view of neoliberals, where the consideration of corruption and influence peddling is banished to the memory hole, Alinsky’s world view was that societal problems often have a strong component of corruption. That view was shaped by living in Chicago in the ’30s, where Alinsky did his doctoral dissertation on Al Capone’s mob during Prohibition. He gained a unique, first-hand glimpse of just how totally corrupt the American system can become. He said of Al Capone, “Forget all that Eliot Ness shit… the Federal Government …couldn’t touch their power…When one of his boys got knocked off there wasn’t any city court in session because most of the judges were at the funeral and some of them were pallbearers.”

The essence of the reason why one should not use local people as “enforcers” was summed up in a story by Saul Alinsky about an incident that occurred while he was working on his doctoral dissertation. In the process, he was adopted by the mob and allowed to freely examine their books and records. One day he noticed that although Capone had 20 hit men on his local payroll, the mob paid $7,500 to bring in out-of-town killers for local hits. He innocently asked Frank Nitti, Capone’s top “enforcer,” why they wasted their money like this.*

Nitti was shocked at Alinsky’s ignorance. “Look kid,” he said patiently, “sometimes our guys might know the guy they’re hitting, they might have been to his house for dinner, taken his kids to the ball game, been the best man at his wedding, gotten drunk together. …one of our boys goes up…he knows …there’s gonna be a widow, kids without a father, funerals, weeping—Christ, it’d be murder.” Alinsky said Frank was a little disappointed by his even questioning the practice; Frank thought Alinsky was a bit callous and insensitive.

The common-sense insight that outside people are more suitable enforcers has been forgotten as the environmental community becomes increasingly drawn into consensus and partnerships, which will supposedly replace, at least partially, the existing “outside” federal enforcement of national environmental laws. Where will environmental protection be if we replace effective administration and oversight of our laws with schmoozy consensus groups and phony partnerships? Will we someday see the control of the Statue of Liberty given over to a local Staten Island “Jobs 2030 partnership” which closes its meetings to outsiders and designates 50% of its board seats to local scrap iron dealers?

No approach can better serve the needs of trans-national corporations, waging a “take-no-prisoners”/win-lose war on the world, than to have its only potential opposition—grassroots social and environmental change activists—adopt a win-win strategy. To adopt consensus-based solutions is a sure-fire way to eventually turn activists into what, in Yiddish, are called “nudniks” (from nudge): people who are always trying to get you to do what they want by constantly pestering and annoying you.

One fashionable myth is that the best way to resolve conflict is through a process of “win-win” which assumes people of good will can sit down and fashion agreements by consensus because “win-win” processes are far more effective than the “old-fashioned” ones. “Win-win” is the basis for the proliferation of consensus decision-making, partnerships and roundtable processes springing up around the country that are favored by most progressive, revolutionary, social justice and left-leaning groups around the world.

Consensus decision-making eschews old-fashioned voting, motions, and the baggage of Robert’s Rules in favor of what are thought to be more participatory, emancipatory, modern, and more democratic processes. But environmental activists are reporting dissatisfaction with the results of these processes, and no general theory of what may be going on has emerged. Saul Alinsky, the father of modern grassroots community organizing and the leading social activist of our time said, “This liberal cliché about reconciliation of opposing forces is a load of crap…the general fear of conflict and emphasis on consensus and accommodation is typical academic drivel. How do you ever arrive at consensus before you have conflict?”

Notice that Alinsky used the words “typical” and “cliché” to describe the approach we now generally refer to as “win-win.” Whenever grassroots organizers become effective, they have always come under intense pressure to stop their activism, cease organizing, stop fighting and join in cozy, schmoozy, consensus groups where powerful people can stroke them, and convert formerly effective activists into house pets. It is a classic strategy because, as Alinsky observed, there are always some activists around who are “too delicate to exert the necessary pressures on the power structure,” who rely “on altruism as an instrument of social change…a fatal mistake of white liberals.” His advice, for the “too delicate,” as he tactfully put it, was to just “get out of the ball park.”

Of course, avoiding consensus processes does not mean there can never be reconciliation, but Alinsky warned, “Reconciliation means just one thing: When one side gets enough power then the other side gets reconciled to it.” He does not mean that activists must never cooperate or compromise; quite the contrary, no one involved with politics can get their own way all the time. There is always a need to compromise. Alinsky said, “My opposition to consensus politics however, doesn’t mean I’m opposed to compromise: just the opposite. In the world as it is, no victory is ever absolute.”

There is a time and place for every negotiating strategy; but we are still in the middle of the conflict stage of environmental activism and the other side is not yet reconciled to us, so we are not ready for the next stage of compromise.

The approaches to decision-making based on “win-win,” partnerships, roundtables, and consensus groups are part of a larger “leadership movement,” which has become popular at the major schools of business administration, where it has percolated into every aspect of public sector leadership training, from the Harvard and Wharton schools of business to the U.S. military. When this movement was emerging in the ’90s, Benjamin Demott wrote an insightful article in Harpers (Dec. 1993), “Inside the Leadership Studies Racket”:

Leadership-cult top dogs have managed, in short, to convince bottom dogs as well as themselves that the country’s problems stem not from evaded issues of injustice or inequality but from technically faulty administration.

The …cant is that of America as the land of happy consensus…seemingly profound and fiercely articulated social conflicts in this country actually are figments, that all good Americans share a feeling for the Universal Unwritten Understanding in the Sky, and that if people of intelligence will but consent to work together, no so-called serious political or cultural issue need ever be joined.

One reason for this vision’s current vitality is the arrival of neoliberalism—the Clintonian gospel slyly proclaiming that Harvard/Rhodes slickness can negotiate any domestic—or foreign-policy issue into nothingness…The two operative political fantasies here which are shared by ‘enlightened’ corporate types, hold that: (1) there are no major differences of interest in American society demanding fair settlement; (2) ways of evading the responsibilities and entailments of a democratic political system can always be found. The new key to successful evasion lies in teaching upcoming generations, from fifth grade onward, to pretend that the key explanation for urban disasters like many of America’s inner cities is that the residents were never properly trained in conflict management and team building.

The theoretical assumptions of neoliberalism about politics, human nature, democracy, and conflict resolution are in complete conflict at every point with the theoretical and working assumptions of indigenous people’s movements, and environmental activists. These conflicts are deeper and more profound than any superficial differences between, say, Republicans and Democrats, or liberals and conservatives. Many activists have learned after it is too late that once these “partnerships,” and roundtable processes have gained a foothold, traditional activism cannot continue to co-exist within the same activist organizations, and perhaps may not even be able to coexist within the same local communities.

This is because the implicit assumptions of neoliberalism and activists are so incompatible they cannot be simultaneously sustained in the same person or organization. These assumptions include ideas such as:

- negotiating can solve all problems, no matter how intractable, because

- profound social conflicts are imaginary constructs;

- the root of any problem is never to be found in waste or corruption, so it is not profitable to ever examine systemic malfeasance; and

- social problems are due to an absence of professional conflict resolution techniques.

Of course, the biggest assumption is that reasonable people working together can solve all problems and discover “win-win” solutions, and that partnerships and working groups can change people’s attitudes since people are all deep down basically of good will and open to new ideas if presented in a cooperative, problem-solving setting.

Alinsky utterly rejected this last assumption and told a story that explains why:

I attended a luncheon with a number of presidents of major corporations who wanted to ‘know their enemy.’ One of them said to me, ‘Saul, you seem like a nice guy personally, but why do you see everything only in terms of power and conflict rather than from the point of good will and cooperation?’ I told him, ‘Look, when you and your corporation approach competing corporations in terms of good will, reason and cooperation instead of going for the jugular, then I’ll follow your lead.’ There was a long silence at the table, and the subject was dropped.

If we are to have political accountability and educate the public to ensure that we do not allow the same mistakes to occur over and over again, we must expose the causes of our problems and air them thoroughly in the media. The mantras of “mistakes were made,” or “we should not point fingers,” or “we need to move forward with solutions,” are the surest way to conceal the root causes of our problems. If the air traffic safety board took this approach when investigating airline crashes, we might well see press conferences where the FAA refused to discuss the causes of a crash, and insisted that we need to avoid unproductive finger-pointing, work for positive solutions and not simply dwell on past mistakes.

If our S&L regulators had used a tad more “win-lose” and a little less “win-win” in their approach to the banking industry in the 1980s, we might have avoided the trillion-dollar looting that subsequently occurred following the 2008 crash. If past court decisions are any guide in dealing with environmental problems caused by corruption, influence buying, or malfeasance, we certainly need the fullest disclosure and exploration of root causes and the naming of names. Alinsky said, “We want to use (organizing) as a means of social and political pressure against the mega-corporations, and as a vehicle for exposing their hypocrisy and deceit.”

Another wheel on the “win-win” bandwagon is the idea that whenever serious conflict arises, there is a strong moral imperative for reasonable people to sit down and work out a “win-win” or common-ground solution. Sometimes, of course, this is the perfectly appropriate path, but not always, and particularly not when deliberate or systematic law-breaking is a major factor in the conflict. (One hopes that if you call a 911 dispatcher to catch a burglar in your basement, the police will not dispatch a conflict mediator to your house).

Our history from the Revolution forward provides abundant examples that justice and liberty are sometimes best served by absolutely refusing to sit down and find “common ground” and “win-win” solutions. In fact, it is arguable that of most turning points of history, where great issues of human freedom were at stake, in-your-face confrontation saved the day. On the other hand, when confrontations were resolved with “win-win” solutions, as Chamberlain agreed to in Munich on the eve of World War II, the greatest human calamities have ensued. The circumstances leading to the desegregation of Little Rock schools in the 1950s provide a good an example of this fact of life and there are many more.

On the eve of Eisenhower’s decision to send 1,000 armed paratroopers into Little Rock to enforce court-ordered desegregation in the public schools, the U.S. House and Senate were overwhelmingly against Ike’s strong stand, as were virtually all the voters, politicians and newspapers in the South. Ike was being warned of uprisings and the imminent abolishment of the public-school system in Arkansas, which would leave black children with no education at all.

During this conflict, Governor Faubus asked Eisenhower if they couldn’t try to find a cooperative approach, perhaps to integrate the lower grades at first and work up to the higher ones over time. Faubus offered to concede all the important constitutional principles which were at stake, i.e., federal law is preeminent over state law, states must follow federal court orders, etc. The governor said he simply wanted a little flexibility in implementation so the public could accept this massive social change for which they simply were not ready.

What was Eisenhower’s response to this seemingly reasonable request to sit down and try to negotiate in the hopes that some “common-ground” could be found?

He refused.

Ike said, “… the Federal Constitution will be upheld by me by every legal means at my command.” A few days later he sent armed paratroopers into Arkansas. He also federalized 20,000 Arkansas National Guardsmen so the governor would not get any ideas about using state troops to oppose Eisenhower’s federal ones. And what happened? The governor backed down, the schools were integrated, and nobody else in the South gave Eisenhower much trouble with school desegregation after that.

- Saul Alinsky quotes are from his last interview given just before he died. “Empowering People, Not Elites:,” Playboy Magazine, March 1972

This is an excerpt from my book Organize to Win Vol 3 which can be downloaded for free from Britell.com

Subscribe to my blog

Download Organize To Win Vols 1, 2, & 3

My Amazon author page